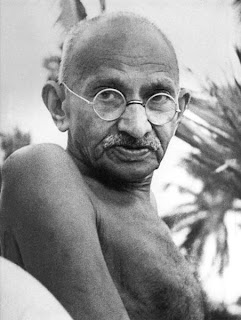

Mahatma Gandhi was born as Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi on 2nd October 1869. He was the most popular as well as the most influential political and spiritual leaders of India. His contribution to the freedom struggle of India is priceless and the country owes its independence, partly, to this great man. The Satyagraha movement, which led to India's independence, was founded by Mahatma Gandhi only. In India, Gandhi is known as the 'Father of the Nation' and his birthday is celebrated as a national holiday. Read on to explore the life history, story and biography of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi:

Early Life:Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born in the Porbandar city of Gujarat, to Karamchand Gandhi, the diwan of Porbandar, and his wife, Putlibai. Since his mother was a Hindu of the Pranami Vaishnava order, Gandhi learned the tenets of non-injury to living beings, vegetarianism, fasting, mutual tolerance, etc, at a very tender age. Mohandas was married at the age of 13 to Kasturba Makhanji and had four sons. He passed the matriculation exam at Samaldas College of Bhavanagar. In the year 1888, Gandhi went to University College of London to study as a barrister.

He came back to India after being called to the bar of England and Wales by Inner Temple. In 1893, he accepted a yearlong contract from an Indian firm to a post in Natal, South Africa. There, he faced racial discrimination directed at blacks and Indians. Such incidents provoked him to work towards social activism.

Participation in Indian Independence Movement:Gopal Krishna Gokhale, a leader of the Congress Party, introduced Mahatma Gandhi to the Indian issues, Indian politics and the Indian people. Gandhi participated in the following movements related to India's freedom struggle:

Champaran and Kheda Satyagraha:The Champaran Agitation and Kheda Satyagraha of 1918 was the first major success of Mahatma Gandhi in his struggle towards India's freedom. The reason for the agitation was the levy of an oppressive tax by the British, which they insisted on increasing further. He organized his supporters as well as volunteers to protest against this atrocity and also began leading the clean up of villages, building of schools and hospitals as well as encouraging the village leadership to condemn the numerous social evils affecting the society. Mahatma Gandhi was successful in signing an agreement with the British, wherein the poor farmers were granted more compensation and control over farming.

Non-cooperation Movement and Swaraj:Non-cooperation Movement of Mahatma Gandhi was one of his prime fights against the British. The massacre at the Jallianwala Bagh of Punjab was what instigated him to take this step. After the gruesome incident, he focused himself entirely on obtaining complete autonomy for the country as well as the control of all Indian government institutions. Soon, this movement turned into Swaraj (complete individual, spiritual and political independence). His association with the Indian National Congress (INC) was further strengthened in December 1921, when he was made the executive authority of the party.

Under Mahatma Gandhi, INC was restructured, accepting the goal of Swaraj, having open membership, forming a hierarchy of committees, and so on. He urged Indian citizens to boycott imported goods, British educational institutions, law courts, government employment, and the like. Non-cooperation became very popular and started spreading through the length and breadth of India. However, the violent clash in Chauri Chaura town of Uttar Pradesh, in February 1922, led to a sudden end of this movement. Gandhi was arrested on 10th March 1922 and was tried for sedition. He was sentenced to six years imprisonment, but served for only two years in prison.

Problems in the Indian National Congress:Indian National Congress began to fall apart without the inspiring leadership of Mahatma Gandhi. The party split up into two groups, one led by Chitta Ranjan Das and Motilal Nehru and the other led by Chakravarti Rajagopalachari and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. Even the basis of the non-violence campaign, the cooperation amongst Hindus and Muslims, began to break down.

Salt Satyagraha and Dandi March:During the period of 1920s, Mahatma Gandhi concentrated on resolving the wedge between the Swaraj Party and the Indian National Congress. Around 1928, Gandhi again started focusing on Indian freedom struggle. In 1927, British had appointed Sir John Simon as the head of a new constitutional reform commission. There was not even a single Indian in the commission. Agitated by this, Gandhi passed a resolution at the Calcutta Congress in December 1928, calling on the British government to grant India dominion status. In case of non-compliance with this demand, the British were to face a new campaign of non-violence, having its goal as complete independence for the country. The resolution was rejected by the British.

The flag of India was unfurled in Lahore by the members of the INC on 31st December 1929. January 26, 1930 was celebrated as the Independence Day of India. Soon, British government levied a tax on salt and Salt Satyagraha was launched in March 1930, as an opposition to this move. Mahatma Gandhi started the Dandi March with his followers in March, going from Ahmedabad to Dandi on foot, to make salt himself. The campaign became so successful that British ended up arresting over 60,000 people who participated in the March. Gandhi-Irwin Pact was signed in March 1931, where the British Government set all political prisoners free as an exchange for the suspension of the civil disobedience movement.

Quit India Movement:As the World War II progressed, Mahatma Gandhi intensified his protests for the complete independence of the Indian subcontinent. He drafted a resolution calling for the British to Quit India. The 'Quit India Movement' or the 'Bharat Chhodo Andolan' was the most aggressive revolt of the INC, with the aim of gaining complete exit of the British from India. Gandhi was arrested on 9th August 1942 and held for two years in the Aga Khan Palace in Pune. There, he lost his secretary, Mahadev Desai and his wife, Kasturba. The Quit India Movement came to an end by the end of 1943, when the British gave hints that complete power would be transferred to the people of India.

Freedom and Partition of India:The independence cum partition proposal offered by the British Cabinet Mission in 1946 was accepted by the Congress, inspite of being advised otherwise by Mahatma Gandhi. Sardar Patel convinced Gandhi that it was the only way to avoid civil war and he reluctantly gave his consent. After India's independence, Gandhi focused on peace and unity of Hindus and Muslims. He launched his last fast-unto-death in Delhi, asking for all communal violence to be stopped and the payment of Rs. 55 crores, as per the Partition Council agreement, to be made to Pakistan. Ultimately, all the political leaders conceded to his wishes and he broke his fast by sipping orange juice.

Assassination:

The inspiring life of Mahatma Gandhi came to an end on 30th January 1948, when he was shot by Nathuram Godse. Nathuram was a Hindu radical, who held Gandhi responsible for weakening India by ensuring the partition payment to Pakistan. Godse and his co-conspirator, Narayan Apte, were later tried and convicted. They were executed on 15th November 1949.

Gandhi's PrinciplesMahatma followed as well as preached the following principles throughout his life:

- Truth

- Nonviolence

- Vegetarianism

- Brahmacharya (Celibacy)

- Simplicity

- Faith in God

.jpg)